'Have Time, Will Travel' - Best Picture Winners We Might Have Missed

Every year there’s one movie that takes home the pivotal Best Picture award, the hype, the press and the sensation of it all might fade but the movies aren’t going anywhere. And the history around the category enables us to skim through the years of nominees and winners as a self preserved time capsule reflecting the evolution of movies.

The Life of Emile Zola (1937)

As the title implies, this is about the life of Emile Zola, the famous writer (played by Paul Muni) whose pivotal text 'J'accuse ...!' (or 'I Accuse') played a part in the Dreyfus Affair. The Life of Emile Zola and all of its instructive implication is a solid movie; given the nature of the content (wrongful imprisonment and anti-semitism), we have a delineated structure and conflict with historical relevance to boot. While the nature of prejudice isn’t directly addressed (I don't recall the words "Jewish" or "antisemitism" ever being uttered), this might account for the low visibility rate among other Best Picture winners. The Life of Emile Zola is a well-made title anchored by a terrific performance from Paul Muni. What was formerly referred to as a “biography drama” is astonishing in contrast to the progress of cinema when we see how little some elements in film simply don’t change. Hindsight shouldn’t reduce what is well made, well-intended film.

Rebecca (1940)

The significance here is not that Rebecca is so much an overlooked best picture winner but is symptomatic of the category and it’s erratic tendencies in nominations and wins. Ironically one of the basic trivia points for Hitchcock is that he never won an Oscar, technically that is. Rebecca kicked off Hitchcock's career in America and while the film is a masterpiece, his relationship with magnate producer David O. Selznick was rife with disagreements and saber rattling over creative control. In the Hitchcock canon, Rebecca isa lesser mentioned title, with all of the director’s classics it feels like the film received favorable attention from the Academy because it wasn’t a genre film (or “conventional” thriller) from the master of suspense, enabling the voting body to embrace Hitchcock’s gifted talents in the form of a classy Du Maurier adaptation. Probably one of the most difficult productions for the director and yet it won Best Picture, however this is when the film's producers took home the Oscar for this category, Hitchcock must have hated this guy. After Rebecca, Hitchcock would be nominated four more times with Lifeboat, Spellbound, Rear Window, and Psycho with no wins.

How Green Was My Valley (1941)

A truly excellent and lyrical film from John Ford that has taken many unjustified beatings over the years simply because it’s not Citizen Kane. Sure, this is one of the most noted, and most likely the first of the Best Picture snubs in Academy history, but in historical context Citizen Kane’s revival wasn’t for fifteen years after it's release - the case for Welles is that the downside to brilliance is that it sometimes takes people time to catch up. However we’ve read, heard and talked enough about Citizen Kane. John Ford’s distinguished career has many great moments and How Green Was My Valley is one of his many great achievements, and in revisiting the film it’s hard to find a glint of reason as to why Ford’s movie shouldn’t have won Best Picture.

Hamlet (1948)

Laurence Olivier’s thread of Shakespeare adaptations were (and in some circles still are) the gold standard for Shakespeare adaptations, and Hamlet might be his best. While I must admit it’s a hard call to make given the strength of Henry V and Richard III, in tandem with my personal weakness for that sumptuous Technicolor photography; but Hamlet is entirely befitting of its moody contrasty photography and weightless camera movements. Olivier’s stately acting notwithstanding, it feels as if a part of his legacy is that he wrote, produced, directed and starred in these three superbly made movies thus making Olivier look like the classiest actor of all time. The expressionist atmosphere makes this dark fable a thoroughly externalized and moody affair, while Richard III and Henry V have a vivid color palette, Hamlet is a pivotal breaking point from stagey reenactments to elegantly stylized works of cinematic art. This was also one of the first British films to win Best Picture, as well as being an inspiration and personal favorite of Roman Polanski.

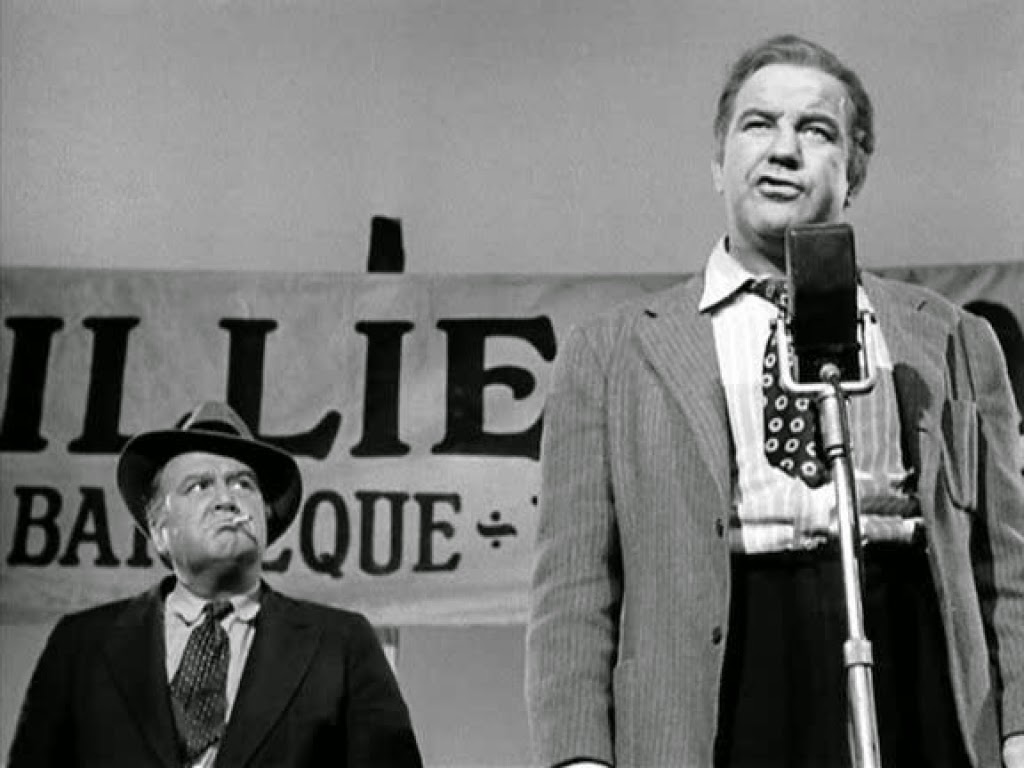

All the King’s Men (1949)

Willie Stark gets into politics as a grassroots idealist; fighting for the people, rallying against corruption, what a great guy, right? Except that this seemingly optimistic slice of Americana becomes a hard driven political film noir when Stark becomes a product of his environment transforming into the worst of crooked politicians. Directed by Robert Rossen (of The Hustler fame), All the King's Men is an unexpectedly swift, and tough-minded film that feels light years ahead of its time, and of course, as our contemporary system worsens, movies like this sustain their relevance. Considering the edge and tone of this film, I’m surprised that All the King's Men isn’t a bigger topic in the conversation of Best Picture winners and movies in general. Not to mention the flimsy 2006 remake, not enough spark to ignite the faintest interest in the original, an obligatory expectation with classic movie remakes.

Oliver! (1968)

A curious winner in an even more curious series of 1968's Best Picture nominees, Oliver! might seem like another saccharine musical from the twilight of the studio system. Having said that, Carol Reed expertly helms a handsomely mounted musical adaptation of the infinitely famed Dickens tale. While I reluctantly admit that I had unjustly likened Oliver! alongside other big, dumb, musicals from the end of the sixties like Hello Dolly!, My Fair Lady, or Paint Your Wagon - it’s a justifiably great film. There’s a little grit in Carol Reed’s iteration, balanced with appropriately embellished musical flair; the juxtaposition of musical numbers against child slavery and London’s underworld. Slightly marred by over length, Oliver! Is one of the last of the great “old fashioned” studio musicals; the following year the Oscar would go to Midnight Cowboy, ushering in a new era in filmmaking as the American New Wave was taking over Hollywood.

Terms of Endearment (1983)

When James L. Brooks is on point, he’s capable of truly fantastic filmmaking, and the double hit of Terms of Endearment and Broadcast News are proof of his brilliance. While the later has enjoyed something of a resurgence thanks to a Criterion release, it’s kind of ironic that his best picture-winning 1981 film Terms of Endearment feels a tad overlooked. The loose fitting but life-affirming tonal treatment is the power of Brooks’ dramatically rich comedic lensing of life. People come and go, they fall in and out of love, they might not always solve their problems, but there’s the shared feeling of experience; as if to say “it’s okay if you don’t have it figured out, no one does.” We see some magnificent performances, Shirley Maclaine's perfect as the shrewd but admirably strong-willed mother, Debra Winger is so human, so spontaneous and so endearing, a young Jeff Daniel’s brings life to an endearingly boyish intellectual. But Jack Nicholson’s philanderer ex-astronaut performance is a marvel he’s as energetic and tenacious as ever, but he’s not overplaying it. Terms of Endearment is light, evident of the time it was and which is precisely why it’s not always on the tip of our tongues which is a shame.

Kramer Vs. Kramer (1979)

A perfectly well made, superbly acted film that has not endured the passing of time too well. The most glaring irony is that the movie feels less urgent with rapid escalation and commonality of divorce; if anything wouldn't that make the themes explored in Kramer Vs. Kramer more relevant An issue that might not seem as “urgent” is still relevant in the arena of dramatic context, and the performances from Dustin Hoffman, Meryl Streep, and (at the time) child actor Justin Henry. If a film isn’t as topically pertinent, don’t let that reduce its narrative power.

Dances With Wolves (1990)

Like How Green Was My Valley, Dances with Wolves’ biggest offense is that “it’s not Goodfellas.” Did it deserve an Oscar for Best Picture? I would certainly say so, but Dances With Wolves is an entirely appropriate candidate for Best Picture, as well. The biggest irony is that snubs and winners are usually on complete opposite sides of the spectrum. Here we have a lyrical epic, that is just as much an homage to the great Hollywood fables as it is a revisionist western. Dances With Wolves has the effusive Americana of John Ford, the scope of David O. Selznick, and modern, sympathetic purview to the history of American natives. Dances With Wolves is frequently referenced as a "white savior" film, and yet this is one of the first (not the first) westerners to have portrayed natives respectively, with their language intact (there are some disputes regarding the scenes in Lakota) portrayed by a cast of indigenous actors. Sure, there is a white Civil War soldier at the front of the story, but Costner’s film (a directorial debut which is weird when you think about it) seems to take a few lashings too many for being as good as it is.

Whether or not you agree with the Academy’s decisions or voting body the ceremony is a celebration of the movies, it’s exciting and suspenseful and there’s a connective quality about it that brings people together every year.