Pacific Rim's Drift Through Memories

Nostalgia isn’t merely in fashion. It is the defining style of the decade. Boot up Netflix and Stranger Things and Fuller House announce themselves as premiere features of the service, and re-boots aren’t created because of concept, but name. Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom is enough to cement the Pavlovian ideal of theme-music, logo, and familiar imagery causing convulsive fits of excitement and instant salivation. The rebranding and re-tooling of ancient styles and texts suggests an unwillingness to move forward, but as prominent as it is, the comfort inherent to many films in the 2010s decade has found an audience which is beyond mass-mongering.

Guillermo Del Toro’s filmography strikes a nerve unlike franchise fare and deliberate homage, as he is never milking the genres he dabbles in or its overt stylistic tendencies, instead playing around in his own child-like sandbox for the sake of his own excitement. The results are hit-or-miss, generally, with the Hellboy films and The Shape of Water adding up to very little besides design eccentricities and operatic elements, but then again, the latter recently won the Academy Award for Best Picture, so the acclaim for his work is undeniable. Influence is everything, and while Del Toro is influencing young, inspiring filmmakers with his passion, he himself is steered by the pure bubbles of love that rise out of his heart.

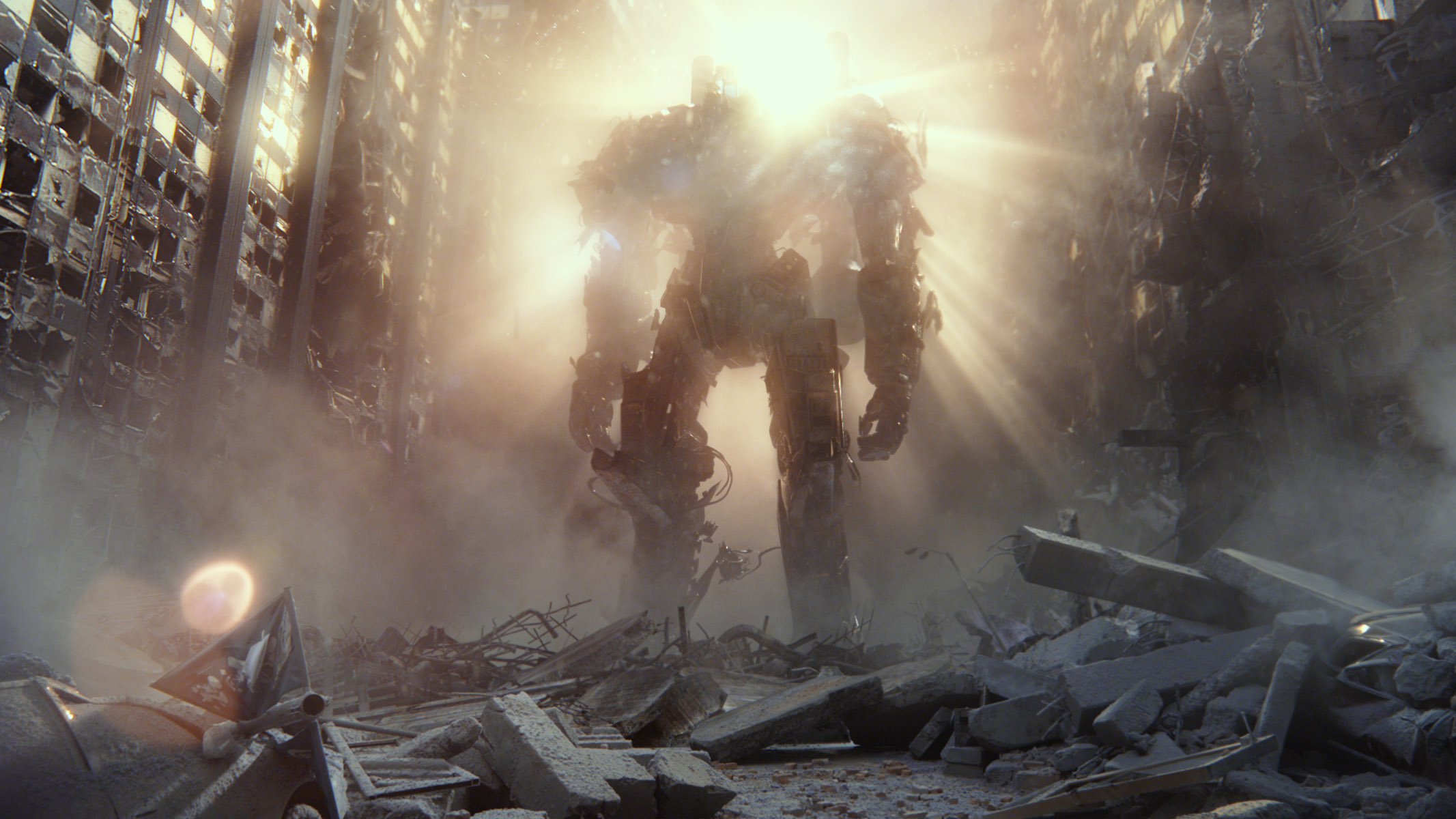

Pacific Rim is the largest, fullest burst of nostalgia that he’s ever manufactured, even despite The Shape of Water fondly remembering the innocent combination of old-school sexuality and love between a woman and a black-lagoon creature. Based on Japanese manga and animation, '50s B-movie monsters, the '60s Godzilla showdowns, and apocalyptic special-effects extravaganzas, the 2013 Jaeger/Kaiju epic was largely criticized for broad characterizations, a predictable narrative, and reveling in its outrageous special effects.

These are not disputable traits, but they reveal the mindset for consumable nostalgic media, and how modern audiences accept the past *only* when recent modes of plotting and sensical development come along for the ride. Pacific Rim does no such thing, staging its action *around* the melodrama, and allowing the growth of the ensemble to develop on its own. Sure, the stock archetypes – the sullen general, the adopted daughter, the stoic lead, the egotistical soldier, the wacky scientists – don’t offer much of anything, but the film treats them with great importance. Just like the exposition dumps of the science/medical/military teams of a Gamera picture, it is filler, albeit marvelously entertaining. It’s a teachable film, showcasing the ropes of how to view it, and the steps to enjoy it more thoroughly.

Performance and action are the two key components of allowing the nostalgic emulation of Pacific Rim to succeed. Charlie Hunnam hardly provides more than a smile, and when his stone-exterior blows past ‘concerned’, it’s wildly unconvincing and wholly purposeful for the lame, undeniably sculpted lead role found in any monster flick. Idris Elba, Charlie Day, Rinko Kikuchi, and Burn Gorman, in contrast, are obviously more interesting, fulfilling their simple duties while overblowing their antics, although the common trait is ‘functional’ in pursuit of the action. And while Pacific Rim has action in segments, they are sustained and prolonged, built to further narrative and the stakes of the end-of-world tension.

Unlike its non-Del Toro helmed sequel, the set-pieces don’t disrupt the drama, they enhance it, and serve a place in the puzzle, not providing the entire answer key. Within the famous Hong Kong battle right in the middle of Pacific Rim, supporting players die, resolve their differences, reveal previously unknown plot information, and (of course) smash a city to shreds. Plot doesn’t slam to a halt when Jaegers and Kaiju start butting heads – it moves along to the complimentary beats of metal and alien monster flesh. Del Toro has great affection for genre (what else is new?), and yet, his most loving tribute is evoking how certain movies move and visualize themselves, tossing in minimal, mandatory technological updates and letting the rest conform to history.

It’s why Pacific Rim will be a seminal film for many younger viewers as they grow up – it is a stepping stone for budding genre-addicts to be accustomed to rhythms of monster movies and sci-fi excursions, all with a smooth finish of cutting-edge effects and expert scale. Del Toro allows himself to stare in awe toward his past, but his audience sees both a nostalgia and a future, evoking our history while carving something new. The first image of a Kaiju in Pacific Rim storming over the Golden Gate Bridge is one which recalls Godzilla and War of the Worlds. The image itself, however, is iconic by its own weight and ingenuity, and it’ll inspire those looking up at the screen just as the ancient monsters of the cinema inspired Del Toro.