Something Has Survived: The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997)

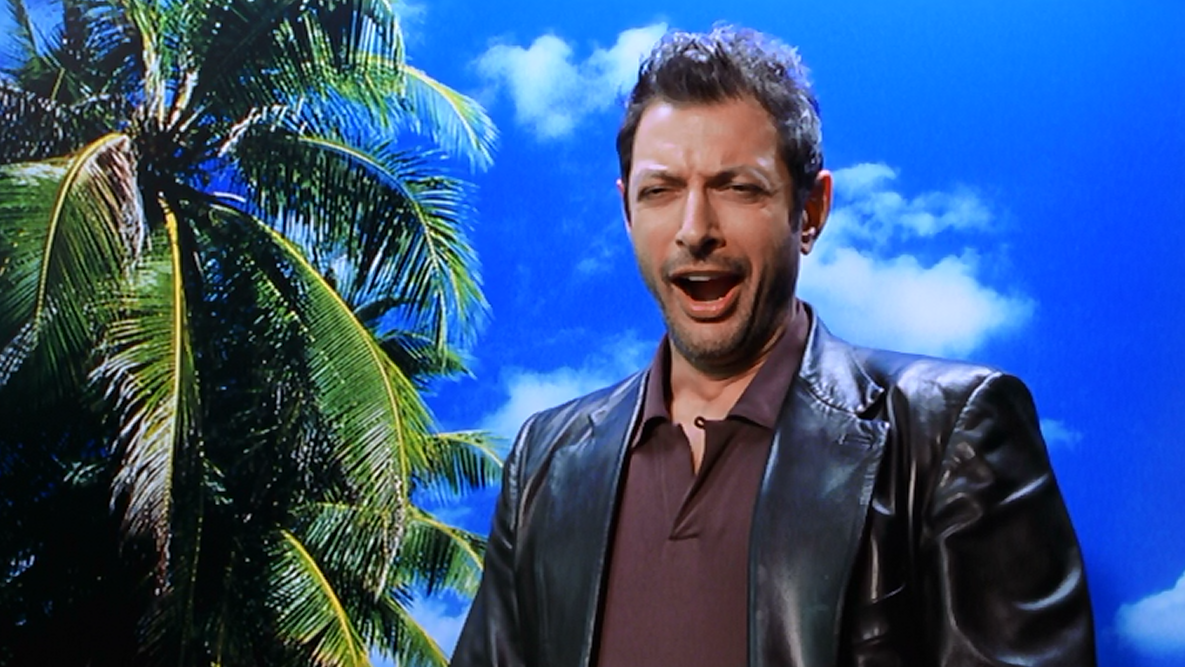

The only moment equivalent to the original Jurassic Park in 1997’s highly-anticipated sequel The Lost World: Jurassic Park is the opening scene. Of course, we’re not talking about content, characterization, or world-building here, as in that sense, Spielberg’s sequel is quite coherent and fluid in its expansion on the first entry, save for tone. The film’s springboard, showcasing an attack on a little girl while a rich family is having a picnic on Site B, is typical suspense escalation, cutting back and forth from the little girl feeding a pack of tiny ‘chompies’ and quickly being overwhelmed, to her family’s worried state regarding her whereabouts. It’s like an initial stinger to a slasher film, where the first kill launches the drama and the preoccupations of the story. The dinosaurs swarm the little girl, the mother follows her screams, and Spielberg captures her agony as the film deploys an outrageous match-cut between her face and the introduction of a yawning Jeff Goldblum.

Yes. That’s right. A. Yawning. Jeff Goldblum.

Spielberg is a mischievous filmmaker, as if that wasn’t already known. Look at Temple of Doom, where voodoo, evil cults, and human sacrifices by way of heart removal and fire were dabbled in glee, and you only need to think about E.T. to be reminded of Spielberg’s playful joy. Jaws and Jurassic Park fused a little of both, offering awe and terror of the respective creature spectacle, and even his more mature efforts find sadism and heartbreak to be truthful, but emphasized in the narrative. The Lost World: Jurassic Park, in comparison, is far beyond anything the director has made, precisely because it’s so outrageous. That one yawn cut is a sliver in the etching of a mountain – Spielberg, with this 1997 sequel, created a no-holds-barred monsterpiece with a mix of ‘50s/’60s disaster tropes and modern intensity. With The Lost World, the technological advancements are out of the way. The dinosaurs are normalized and replaced by crazy set-piece continuity and viciousness. Spielberg has nothing to prove, so why not make a fucking monster movie?

It’s that sense of childhood glee, not to be mistaken with wonder, that Spielberg spills onto the floor like a box of dinosaur figures. With a greater variety and a vastly larger number of dinos, The Lost World becomes an amusement-park ride of nonstop suspense and set-piece bravura, with Spielberg pacing each like a swiss watch and filling the in-between character dynamics with enough detail and trademark cross-talk to keep the viewer invested. Goldblum and Julianne Moore handle the key dialogue scenes like the champion actors they are, offering a complexity that allows the film to truly become its own thing.

And with that comes the backlash, which to me, is rooted in an inability to accept anything other than the original classic, and little issues are used as “evidence”. Lapses in logic and some embarrassing tidbits aren’t anything new in Spielberg movies, and especially in the Jurassic Park universe (reminder: “it’s an interactive CD-ROM!”), and The Lost World mutes any problems with a deafening T-Rex roar.

Take, for instance, the connective tissue from the T-Rex campsite attack to the raptor ‘long-grass’ scene, to the elongated showdown in the abandoned base. Spielberg tracks each segment with precision, never allowing suspense to drain and yet keeping a distinct feeling for each. No one is safe in The Lost World, which is a lot different than the park in Jurassic Park keeping things relatively secluded. The landing of the T-Rex in San Diego is triumphant and terrifying because it’s a culmination of the film’s focus being on our interactions with these creatures, and how apathetic they are towards our existence. Early on, in a beautiful snapshot turned ugly, Moore’s character gets close to a baby stegosaurus, and soon finds the mother is very protective. The ferocity of the mother attacking those who get close to her young mirrors Goldblum’s yearned safety for his daughter, and the film highlights the small circles of trust and protection we all have for family and loved ones. Outside of that circle, however, is a meaningless construct of death and despair, and The Lost World depicts that too, capturing the disposable nature of man and the inability to learn from our mistakes.