We Always Have a Choice: Revisiting Spider-Man 3 on its 10th Anniversary

It’s hard to deny that Sam Raimi’s 2002 blockbuster Spider-Man kickstarted the superhero genre that dominates the worldwide box office nowadays. It was such a critical and financial success for a number of reasons: it was centered around a refreshingly mundane everyman rather than the 6-foot-tall, toned-bodied action figures that lead the comic book movies of years past, it’s wide-eyed heroism cultivated the same sense of hope that fans felt on every page of the best Spidey comic interaction, but most importantly—in a concept that feels like a rarity as we ease toward the third Thor movie in six years—Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man didn’t feel like it was made out of obligation. The film didn’t get made because Spider-Man was set to co-star in an Avengers movie two years later, it was made because Raimi wanted to adapt a comic about a dweeby high schooler who dresses up as a big red spider to defend a city full of people who deserve a hero. It’s a simple story about how true heroism exists in the unlikeliest forms, delivered with enough compassion and honesty to make it a timeless classic.

Then, Spider-Man 2 came along the two years after and became and still remains the definitive superhero movie. Spider-Man 2 is among my favorite films not just because it’s a movie that has lived next to my heart ever since I figured out how to rewind the VCR, but because it so beautifully encapsulates the reason that Spider-Man has been so inextricably connected to who I am today. It understands that at the heart of every good Spider-Man story is Peter’s struggle to accept the impossible idea that the financially unstable kid from Queens with social anxiety and the international web-slinging beacon of hope are one and the same, and that Spider-Man isn’t just a guy in a suit, he’s an idea—the idea that we don’t have to get bitten by a radioactive spider to help someone in need.

In the summer of 2007, three years after its predecessor, Spider-Man 3 came out…and people hated it. Like, really despised it. A lot of people turned against Sam Raimi (who hates the film just as much as them) for supposedly “ruining” his Spider-Man trilogy with a final film that, admittedly, is very different from the two previous installments. Spider-Man 3 is…many things, but perhaps the most striking aspect of actually watching it is just how odd this thing is. It’s a really fucking weird movie, where one of the three(!) main antagonists is some douchey kid in his early twenties who’s most likely a men’s rights activist and constantly describes the symbiote that turns him evil as “...good”. But even weirder still, is that in all its resounding messiness, Sam Raimi turns his heavily studio-influenced final installment in the Spider-Man trilogy into a bold, interesting character study of Peter Parker, and it actually sort of works.

Now, I’m not saying that Spider-Man 3 is a great movie—it’s only barely a good one—but it IS good, dammit! The film is jampacked full of shit it would be better off without. Most notably, the three main antagonists all work beautifully on their own, but shoving them all into one movie means that none of them get the focus they deserve. The Sandman is a great character because, like every great Spider-Man villain, he’s just a guy with good intentions and powers he doesn’t know how to use. Peter’s real superpower is not his heightened senses or super strength, it’s the ability to use those powers where they matter. He effectively teaches Sandman, an escaped convict who’s desperately trying to find the money to pay for his daughter’s medical bills, the same lesson that’s so seminal to Spidey’s nature: that some people can’t be saved and that all we can do is help others satisfy their needs in the hopes that we may learn to satisfy our own.

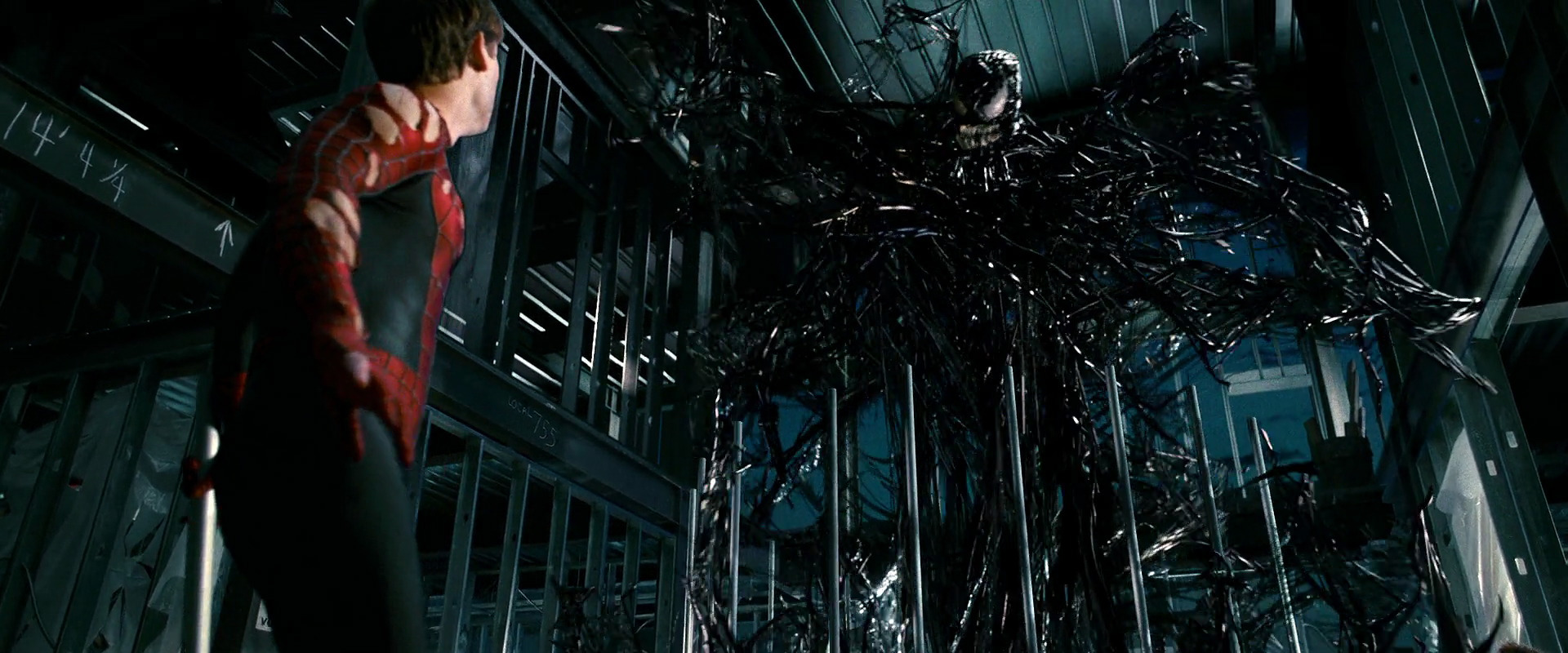

Harry Osborn as the “New Goblin” probably should have been the only antagonist in the film given the trajectory of Spider-Man 1 & 2, and while his arc is heavily sidelined, the way Peter empathizes with Harry’s constant fear of never feeling good enough, even as enemies, is a beautiful thing. The most controversial villain of the film, a symbiote-infected Eddie Brock as Venom, is extremely undernourished. This is understandable, considering that the inclusion of Venom was entirely the studio’s choice, but I will defend the casting of Topher Grace with my life. Most criticism against Topher Grace (praise be) is that he’s the opposite of a threatening villain, and instead just acts like an immature dick the whole movie...but that is exactly the point.

Peter Parker, with all his anxiety and naivete, wouldn’t look like much of a hero taken out of context, but his superhuman abilities, and most importantly his benevolence, are what make him one. Eddie Brock has half of those things—heightened strength and senses but not the altruism that’s necessary to go with it. He can’t do anything right and that’s completely intentional—he can’t keep his job, he can’t respect his girlfriend, and he can’t kill the Spider-Man. It’s fitting that the final foe of Raimi’s Peter Parker is essentially a high-school bully, because those bullies are the ones that Peter swore he’d be better than when he got his powers in the first place. Eddie Brock isn’t just a bad guy to beat up, he’s the bad guy that Peter has always been trying to overcome—he just didn’t know it. Their conflict is not and never was about who’s more threatening, but who is the better man. It’s true here, and it’s true with every great Spider-Man rivalry. Unfortunately, the movie isn’t four hours long and cannot reasonably develop any of these subplots the way they deserve, so they all just exist as great ideas with no room to breathe, resulting in an unrewarding finale.

The film is a mess and constantly disappointing, but Peter’s character work here is too good to ignore, his arc being more mature and just as effective as it was in the Spider-Man films that came before. If the first film is about a hero being born from a city’s collective fears and anxieties, and the second film is about Peter coming to understand what it means to be that hero, then Spider-Man 3 is about Peter forgetting what it means to be a person. The film takes place right when adulthood fully sets in for Peter—both in his job at the Daily Bugle and in his relationship with Mary Jane, who he realizes he cares about enough to marry. It’s fascinating to see how being Spider-Man for so long has made him forget that being a superhero is more than putting on a suit and fighting crime. He’s forgotten how to be vulnerable with the people he cares about, and that’s illustrated beautifully in his failing relationship with Mary Jane. A common complaint many have about the film is in its portrayal of MJ and how she’s presented with a lack of independence, relying too much on Peter for approval. I think that the series has this problem—a majority of the action set pieces begin with Mary Jane getting in imminent danger and screaming a lot before getting saved by Spider-Man. That is no different here—and happens, like, three times—but I disagree wholeheartedly that Mary Jane lacks independence. Her relationship with Peter is more serious, and while Mary Jane has trouble succeeding on Broadway, she’s searching for someone to confide in, and Peter is too busy being Spider-Man and not the person she needs. Their dynamic in Spider-Man 3 is built on their struggle to fully empathize with each other, and Peter coming to realize that he can’t be Spider-Man without friends and family that support him is an extraordinary thing to witness.

In the little explanation given about the Venom symbiote, it’s said that the black goo turns its host into an exaggerated version of their true self. This is a fascinating and ultimately rewarding character choice for Peter, considering that the symbiote turns him into a laughable emo prick. Many think that the film’s infamous jazz scene, in which Peter uses his spidey senses to play a kick-ass piano riff and dance like a dumbass at a jazz club for five minutes, is the film’s worst scene—but I consider it one of the best. It’s a mind bogglingly weird sequence, but it’s important to emphasize that the movie does NOT think that it’s cool. The symbiote infecting Peter doesn’t make him badass nor does it make him edgy in a cool way; it makes him edgy in a Reddit way. It effectively strips the latter half of Uncle Ben’s last words of wisdom to Peter, taking away his “great responsibility” but only increasing his power, leaving him in a position where he must learn that he can’t have one without the other.

The finale may be an unsatisfying finish to the film’s three antagonists, but I’ve always seen it as a fitting end to Peter’s arc. He becomes a better man by learning that neither Peter Parker nor Spider-Man are invincible, and in one of the film’s final shots he watches the sun rise over the Manhattan skyline as he sits with Mary Jane, comforting a near lifeless Harry Osborn, learning to let go of the past as he makes way for his future with MJ. You can’t save everybody but you can hold the ones you love close and hope they stay there. It’s all we can do.

If anything, Spider-Man 3 is a testament to how talented Raimi is. He took what would undoubtedly be a disaster and turned it into something bold, powerful, and entirely worthwhile. He couldn’t save everything, and the film feels like it could be separated into three separate great movies, but I’ll settle for one good one instead. It’s a complicated relationship I have with Spider-Man 3, one that’s left me frustrated more than anything—but rewatching it for the hundredth time exactly ten years after its release, I know for certain that this movie is better than so many give it credit for, and I know for certain that it demands to be taken seriously. Give it a chance. It deserves one.