Finding Joy in Revolution: An Analysis of Janelle Monáe’s Dirty Computer

"The mediator between the brain and hands must be the heart" - Metropolis (1927)

Those familiar with French history may have come across the name Julie “La Maupin” d’Aubigny and the stories that are told about her life. A French icon and legend, La Maupin (her opera name) was a famed bisexual swordswoman and singer who lived in the 17th century and dressed in male clothing. She refused to be forced into marriage and wandered across France with a string of lovers (her most famous being a woman whose parents forced her to be a nun at a convent that La Maupin burned down and helped her escape from) and made money through singing and dueling demonstrations. It can be easy to look at women’s history and assume that the lives of the women who lived before us were solely defined by different forms of oppression and loss. Yet, when closely examined, it’s clear that women have always found ways to rebel against the systems that hurt them, whether it be in direct action or more subtle ways. This was reflected in La Maupin as she was unabashed, rebellious, and lived on her own joyous terms, refusing to accept the traditional role that society gave her, much like Janelle Monáe.

Born in Kansas City to a working-class family, Monáe knew that she wanted to pursue singing from a very young age. After moving to New York and studying at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy, she dropped out and moved to Atlanta where she helped create the Wondaland label and made music that would become part of her Metropolis series. Without context, this portion of Monáe’s work can seem confusing, yet her brilliance is revealed once it’s understood what she is referring to.

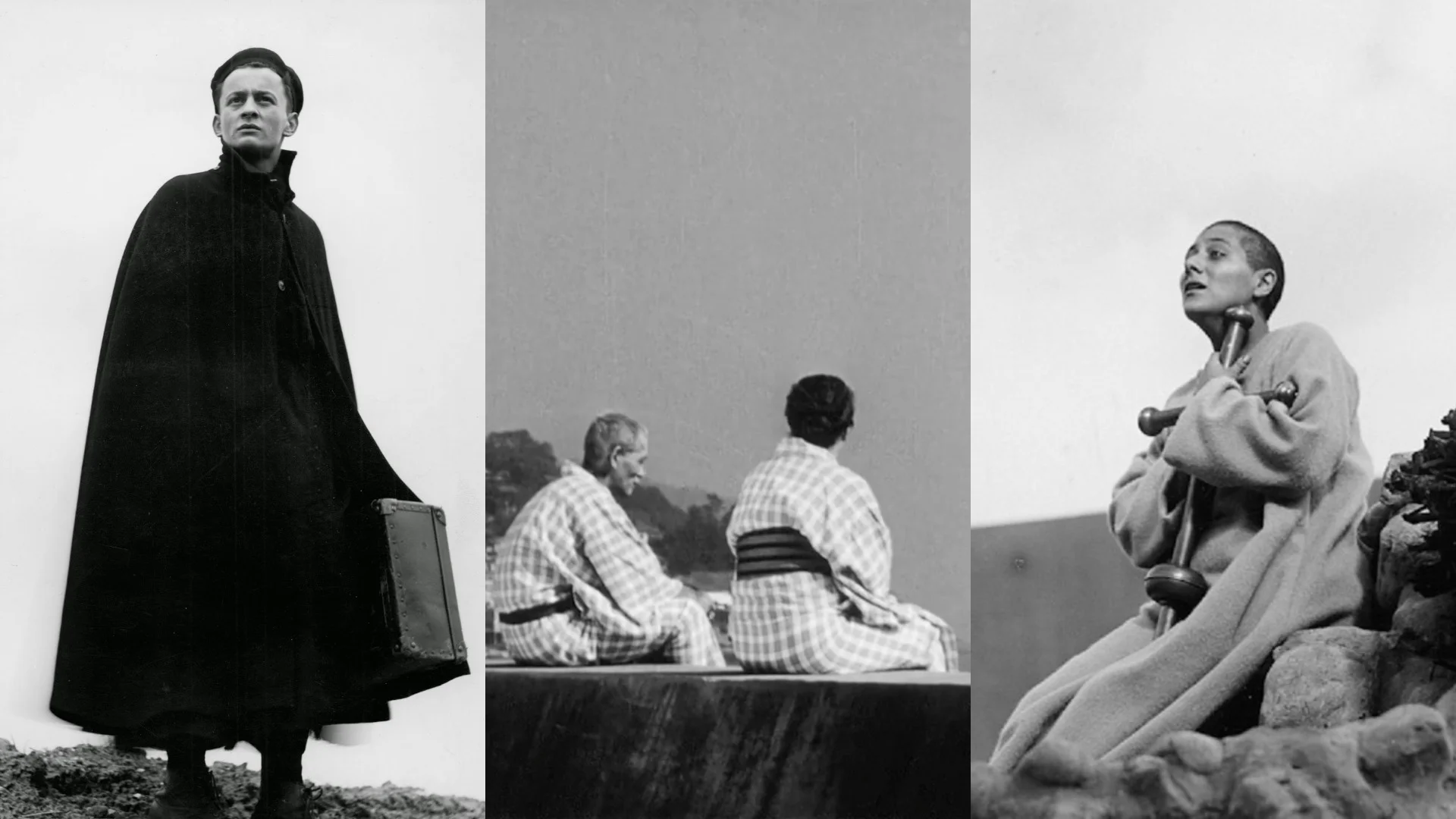

Monáe’s main inspiration for her first three albums is the German Expressionist film Metropolis (1927) which tells a story about a futuristic city built on the backs of exploited laborers and a female android that spurs them on to revolution. Though in the film it is quite clear that the android is a nefarious doppelganger who manipulates the workers into dissenting, Monáe takes this narrative and changes the perspective in her music. Not only does she make it clear that she is speaking from the viewpoint of a black woman, but she also imagines what it would look like if she were the female android sent to liberate the exploited androids in Metropolis. Using themes commonly found in afro-futurism, Monáe takes science fiction (a genre which often imagines the future as patently white and depoliticized) and comments on society today as a futuristic other. She’s stated as much in interviews, “I love speaking about the android because they are the new other.”

Generally, the other is a term used to denote those who have specific characteristics that would cause them to be alienated in society. This is because they do not conform or have the qualities to be what a given society deems normal. Those living in America often find the default to be straight white cis men, and that those who are outside of any of those labels are treated as such. Though in philosophy it is often related to one’s identity, the philosophers Derrida and Beauvoir tied it to social constructs like race and gender, partially explaining why people who fell into these categories were treated differently. It is important to understand this because Monáe builds her musical narratives around the intersections that tie her to the concept. Though she is speaking from the perspective of the Android (whose name is Cindi Mayweather) she’s able to flesh out the world Metropolis depicts and relate it to her experiences as a young black woman. The first album, Metropolis: The Chase Suite, tells the story of how Cindi falls in love with a human named Anthony Greendown and is hunted down to be disassembled because of it. What strikes one right away is that Monáe completely embodies this character and the world she’s trying to build, going so far as to imagine futuristic language that’s echoed in the announcement calling for Cindi’s capture, “Remember only card-carrying hunters can join our chase today/And as usual there will be no reward until her cyber-soul/Is turned into the star commission, happy hunting!” The subsequent song “Violet Stars Happy Hunting!” tells of how Cindi has to run from the police and though it is not overtly political, heavy policing and authoritarianism are themes which Monáe regularly explores in relation to what black communities face in the present day. In fact, the song “Sincerely, Jane” is a lament specifically about the hardships and losses those within Metropolis (and subsequently those today) face, everyone from young women to teachers “Left the city, my momma she said don't come back home/These kids round' killin' each other, they lost they minds, they gone/They quittin' school, making babies and can barely read”

Her subsequent two albums, The ArchAndroid and The Electric Lady both build on the mythos that Monáe created with her first. In The ArchAndroid, along with string interludes, we get more details of Cindi’s life on the run in songs like “Faster” and love affair in “Sir Greendown” and “Mushrooms & Roses”. Generally, Monáe’s musical style is one that combines R&B, Pop, Funk, Soul, Jazz, Classical, and occasionally Rap. Her futuristic themes and craftsmanship make it possible to merge these genres without it becoming overwhelming or tiresome to the listener. Her third studio album, The Electric Lady, is the one that leans the most into the Funk and R&B genres. Here, it is revealed that Cindi has the power to time travel and a lot of the political themes that Monáe previously explored are expanded upon. In the music video for Q.U.E.E.N. (changed from Q.U.E.E.R. to be less conspicuous about Monáe’s sexuality) not only is Monáe frozen inside a totalitarian art museum, but she also makes a couple jabs at religion and the forces that oppress workers and women. This is especially prevalent in the rap at the end of the song, “Add us to equations but they'll never make us equal/She who writes the movie owns the script and the sequel/So why ain't the stealing of my rights made illegal?/They keep us underground working hard for the greedy/But when it's time pay they turn around and call us needy”

This brings us to her newest album and “emotion picture” Dirty Computer. Released on April 27th, it was very clear that this marked a turning point in Monáe’s work as it was a departure from her speaking as Cindi Mayweather. Though Monáe adeptly used the character in order to speak about topics that were important to her, it prevented us from really knowing Janelle Monáe the artist. This album remedies that. Though the film takes place in the future, the message and songs are rooted in the present.

The film itself follows Monáe (known as Jane 57821 in the movie) in a future dystopia where people (known as computers) are hunted down and “cleaned” (their memories are wiped and they are made compliant) of their “dirt” (things society deems aberrant and rebellious). Though the main narrative is about a frightened Jane going through this process, it’s interspersed with her memories, dreams, and desires. The viewer watches as two white men sort through all of these and erase them. This is where we see a careless and joyful Jane partying with her friends, running from the police, meeting new lovers (Tessa Thomson’s Zen and Jayson Aaron’s Che), and embracing her “otherness”. It’s made quite clear that even though she lives under an oppressive regime, this does not stop Jane from defying it by finding happiness and fulfillment. At one point during Jane’s “cleaning”, one of the men argues against deleting parts that don’t seem to be memories and is told to be quiet. These look like Jane’s (and subsequently Monáe’s) latent desires and feelings. In “Django Jane” she angrily raps about sexual violence, misogyny, and injustices that are committed against women. The more abstract “I Like That” features her in unique costumes, unabashed about her tastes and what other people think of them. Eventually, Jane discovers that Zen has also been brainwashed and we see how Jane changes as she undergoes the same process. Though it would appear that the “cleansing” was successful, after the credits there is a short scene where the song “American” plays and Zen (who, surprisingly, has resisted being brainwashed) breaks out of the facility with Jane and Che in tow. “Love me baby/love me for who I am” powerfully plays as Monáe looks into the camera and vanishes out into the sun.

Dirty Computer has been compared to Michel Gondry's Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, but there’s much more going on in the film than Jane’s memory simply being erased, which is where the comparison lies. Jane is being “cleansed” of anything that could make her aberrant: her womanhood, her queerness, her blackness, and her rebelliousness. It is not simply that she inhabits certain intersections, but that those intersections need to be suppressed and erased. Those who are othered in American society have undoubtedly felt this pressure to conform and the fear that comes with really speaking your truth. In a capitalist patriarchy that exhibits sexism, racism, queerphobia, ableism, and classism all around (from one’s aunt to longtime friends) it can be very tempting to give in and become one of the people you oppose, simply to escape the anger, exhaustion, and stress that it brings. Even Monáe herself commented on these same feelings about releasing the album, “This is the first time I’ve felt threatened and unsafe as a young black woman, growing up in America,” she said. “This is the first time that I released something with a lot of emotion. The people I love feel threatened. I’ve always understood the responsibility of an artist — but I feel it even greater now. And I don’t want to stay angry, but write and feel triumphant.” This is reflected in her song “So Afraid” where not only does she talk about being separated from those she loves, but also the anxiety she has about showing the world who she truly is. “Ah, what if I lose?/Is what I think to myself/I'm finding my shell/I'm afraid of it all, afraid of loving you” Those who are queer and politically radical can identify with these same fears.

From being stopped by a police drone to seeing her own friends being kidnapped by the government, Monáe aptly depicts how all-encompassing injustice can be. But there’s a key difference in Dirty Computer that keeps it from becoming torture porn like The Handmaid’s Tale: the pleasure that Jane experiences throughout the whole narrative. This is something that leftists generally need to take note of: resistance can be emotionally taxing and rather than telling stories that make viewers more depressed about our situation (as Arielle Bernstein notes in her recent Guardian piece on The Handmaid’s Tale) we need stories of hope. Monáe’s is not a vague or passive resistance, it’s rooted in reality, in constantly feeling the weight of a world where so many wait to be liberated in a multitude of ways. But the difference is that it gives a reason to resist.

So what about Dirty Computer makes it delightful to watch? I think that question can be answered through ideas prevalent in feminist film theory and aesthetic theory. The first three parts of Dirty Computer that Monáe released were the videos for “Make Me Feel” and “Django Jane” and “Pynk” which all had separate styles but overlapping themes. “Make Me Feel” is drenched in colorful lighting, sparkling costumes, and sexual undertones. Bi-lighting sets the mood as Monáe runs back and forth between Zen and Che, as she’s attracted to both. Though the Dirty Computer’s story involves all three characters, there’s more of a focus on Jane’s relationship with Zen and nowhere is this more clear than in “Pynk”.

The Twitter account Tabloid Art History did a great job connecting the visuals in “Pynk” with past yonic and feminine art. This video is not a masterpiece just because it features Monáe in vagina pants, but also because it celebrates femininity in a way that does not objectify those onscreen. For female viewers, there is a feeling of both safety and radical opposition in the queer overtones and how the female body is embraced. When it comes to aesthetics, feminist film theorists often debate the nature of the necessary actions that need to be taken in order to get rid of film’s visual patriarchal roots. Some say that we need to inject realistic depictions of women into film, others argue that in order to really solve the problem we need to rethink film entirely. In her essay, “Rethinking Women’s Cinema: Aesthetics and Feminist Theory” author Teresa de Lauretis comments on this very debate. Though in this passage she is referring to the movie Born in Flames, she could easily be describing Dirty Computer, “What one takes away after seeing this film is the image of heterogeneity in the female social subject, the sense of a distance from dominant cultural models and of an internal division within women that remain, not in spite of but concurrently with the provisional unity of any concerted political action. Just as the film’s narrative remains unresolved, fragmented, and difficult to follow, heterogeneity and difference within women remain in our memory as the film’s narrative image, its work of representing, which cannot be collapsed into a fixed identity, a sameness of all women as Woman, or a representation of Feminism as a coherent and available image.” In the essay, she also comments on how depicting female queerness onscreen is also a truly radical act, the same idea often being argued in feminist essays like Sylvia Wynter’s “Beyond Liberal and Marxist Leninist Feminisms: Toward an Autonomous Frame of Reference”.

Overall, it is quite clear that even though it did get a wide release in theaters, Dirty Computer is a subversive film with apt political commentary. Wide in scope and inclusive in how it depicts rebels (from hipsters, to punks, to people of different ethnicities), it’s a film which embraces the collective in a society that has the potential to isolate so many. In the wake of America’s ongoing problems with gun violence and toxic masculinity, Monáe advocates for a peaceful rebellion that starts with people finding joy in revolution.