Universal Monsters Week: Frankenstein (1931)

"Look! It's moving. It's alive. It's alive... It's alive, it's moving, it's alive... IT'S ALIVE! Oh, in the name of God! Now I know what it feels like to be God!"

Debuting the same year as Bela Lugosi’s famous Count, Dracula, James Whale’s 1931 classic Frankenstein tackles Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel of the same name. Yet, unlike so many of the other monsters in Universal’s stable, Frankenstein’s story is decidedly different. His tale is a tragedy.

After discovering a ray that can create life, Dr. Frankenstein (that’s the monster’s creator, not the monster himself) dispatches his assistant Fritz to steal a brain from a medical professor who, by luck, has been demonstrating the differences between two brain samples: a healthy brain and a criminal brain. Mid-theft, Fritz drops the healthy specimen and is forced to steal the criminal’s brain from the classroom.

In a way, this silly conceit is really quite brilliant in the way it sets up the tragedy of Frankenstein. Given that we are told about the immutability of the criminal’s mind – the lecture the professor gave was on the physiological differences between the criminal and normal brain, Frankenstein’s Monster’s violent actions become not a product of an impulse that can be controlled or a learned habit, but rather a function of the brain that was slotted into his body.

This tragedy is only heightened by a beautifully potent scene midway through the film that strikes with clarity and sincerity. Frankenstein’s Monster – billed here in the opening credits as only “The Monster” with a casting of “?” (who we now know as the actor inextricably linked to the role: Boris Karloff) – plucks daisies with a young unattended girl by a lake. As she teaches the Monster to toss the flowers in one-by-one to see them float, the Monster takes the next logical step – at least for someone with limited knowledge of buoyancy – and tosses the young girl in the lake atop the flowers. It’s a shocking scene and absolutely drips with tension even before the act is actually performed.

But, perhaps what is most spectacular about this scene is how it builds upon Frankenstein’s Monster tragedy brilliantly. We have seen how Dr. Frankenstein whips, chains, and imprisons the Monster, using him as a demonstration of his own deity-like powers. But, the real tragedy of the character lies in his very nature. Frankenstein’s Monster is made evil, or at least with some evil parts, notably his brain. He can’t be anything but violent because of how he is made.

In the film’s final act, The Monster, trapped inside a windmill with his creator by an angry mob, saves Dr. Frankenstein by tossing the doctor to the ground below as the windmill goes up in flames. It is, once again, a beautiful statement of the Monster’s tragedy. Even when his own life is at stake, his first impulse is to save another.

Though Frankenstein remains potent today, upon its 1931 release in the United States the drowning scene was cut by film censors in New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. In Kansas, nearly half the film was removed before the public screening, including a supposedly blasphemous line – the film’s most famous and oft-parodied, “It’s alive! It’s alive! In the name of God! Now I know what it feels like to be God!”

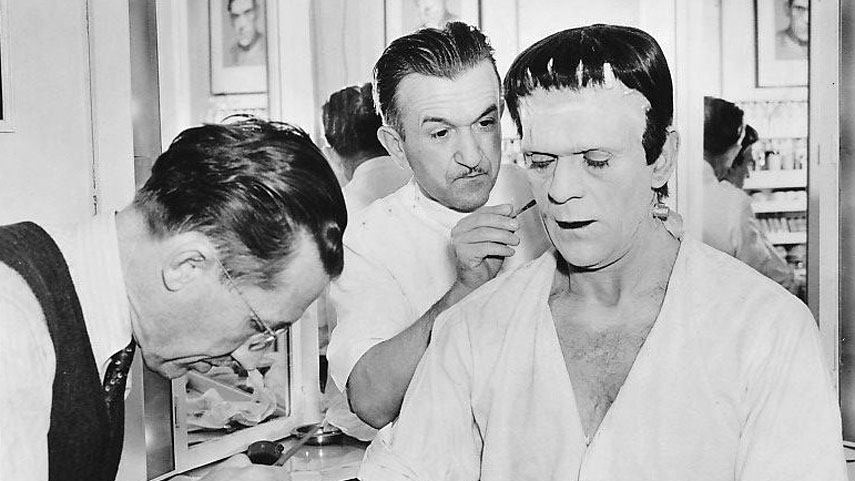

In spite of this butchering, Frankenstein made a huge splash at its 1931 premiere. Its stellar makeup, the performance of the uncredited Karloff, and the almost surreal sets were among contemporary critic’s praise. And indeed, today, all of these elements hold up. The makeup remains grotesque, but even more importantly, it remains iconic. Very few characters are so immediately recognizable as Frankenstein’s Monster. And indeed, very few faces – I would argue none – are ever substituted for Boris Karloff’s in that role.

In spite of the film’s jittery start and stop editing, mostly a product of the technology of the time, Whale’s Frankenstein holds up marvelously. It has become perhaps the most iconic of Universal’s monster stable – along with Bela Lugosi’s seductive take on the Count. It has inspired directors for decades to both tackle Mary Shelley’s tragic character or some facsimile of him. And, with Guillermo del Toro’s long-gestating version of the character perpetually resurfacing in rumors and interviews, we can only hope for a modern Frankenstein half as good as Whale’s original.