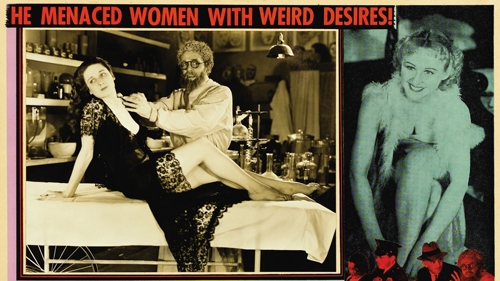

Schlock Value: Maniac (1934)

Hot damn, do I love pre-code films, and if you’re a faithful reader of this column, I’m assuming you do too. In the 1920s and early ‘30s, Hollywood was pretty much the Wild West and films could get away with pretty much anything, including gratuitous nudity, graphic violence, and myriad other things considered unacceptable for viewing by the general public. Unfortunately, in 1934, all of that came to an end for the major studios when the Hays Code became more strictly enforced. Enter: Dwain Esper. Less a filmmaker and more a guy who just happened to acquire some filmmaking equipment, Esper operated outside of the studio system, and specialized in low-budget sleaze and “propaganda” films that offered all of the depravity that the late-night audiences craved.

Up until this point, he had already directed a handful of films including Narcotic, an exploitative cautionary tale “presented in the hope that the public may become aware of the terrific struggle to rid the world of drug addiction.” In addition to the films he made himself, he would also acquire the rights to popular pre-code films including Tod Browning’s Freaks and take them all on the road. But in 1934, just as the MPAA was really starting to come down on this stuff, Esper released Maniac (aka Sex Maniac), a wild little film that is as insane as it is incoherent.

It begins with a big wall of text about the dangers of mental illness and how many people who suffer from a mental illness are at a tremendous risk for criminal behavior. There are a handful of these throughout the film, as though it were some sort of educational film, rather than a piece of exploitation schlock. Apparently, this helped justify some of the more scandalous material. Anyway, we’re then introduced to Dr. Meirschultz, a mad scientist in the vein of Victor Frankenstein or Herbert West, who spends his days working to re-animate human corpses. His assistant, Don Maxwell, is an ex-vaudeville actor who is wanted by the police (it’s not clear why), and now works for Meirschultz, collecting bodies for their experiments.

You see, his vaudeville experience, and talent for impersonation, gets him past the guards at the local morgue. Everything is going more-or-less okay until Meirschultz, who has a re-animated human heart in need of a corpse, asks Maxwell to commit suicide for the experiment. Not ready to check out just yet, Maxwell turns the tables and kills Meirschultz instead. Aware that Meirschultz would be missed, he quickly devises a plan: he will don a pair of glasses and a long white beard to impersonate Dr. Meirschultz and continue his experiments to avert suspicion. Now, this would all be well and good if doing so didn’t drive Maxwell completely insane in the process.

Once in his Meirschultz disguise, Maxwell quickly hides Meirschultz in a dark nook of the laboratory, sealing it off with bricks, but not before Meirschultz’s cat (aptly named Satan) jumps through a gap in the wall (this is important for later). At this point, the film pretty much goes off the rails. Maxwell continues to descend into madness and experiences vivid hallucinations, which are presented in a series of sequences where he flails about wildly while stolen footage from Maciste in Hell, Häxan, and Fritz Lang’s Sigfried is superimposed over the frame, and he begins to behave more and more erratically. In the film’s most infamous sequence, he chases a cat around the lab, eventually catching it, squeezing it’s eye out, and declaring “it’s not unlike an oyster, or a grape” before popping it into his mouth. Fortunately, it was all a well-crafted illusion, and not legitimate animal cruelty. He also begins seeing patients for various medical reasons, which provides an easy excuse to slip a topless woman into the film.

He is eventually visited by a sick man named Buckley whom he injects with Meirschultz’s magic serum, transforming the man into a raging lunatic who, in a wonderful moment of scenery chewing that would make Dwight Frye proud, kidnaps a re-animated woman and runs off through the countryside to God knows where. When Mrs. Buckley realizes this doctor is a killer, she decides, for some reason, that he’s the guy who will find her husband. But before too long, Maxwell becomes paranoid and locks her in his basement.

Meanwhile, across town, there’s a troupe of burlesque performers who are mostly in the movie to lounge around in skimpy clothing. One of them, conveniently enough, is the estranged wife of our protagonist. When she finds out that he is to inherit a large fortune, she somehow seeks him out and ends up locked in the basement with Mrs. Buckley, where they are forced into a fight to the death with hypodermic needles in a filthy rat and frog-infested basement. Pretty soon, the police show up to intervene and guess who they hear meowing through the brick wall.

Look, Maniac is a lot of things, but one thing it is not is boring. From the absolutely ridiculous narrative which borrows pretty liberally from the works of Poe (The Black Cat and The Tell Tale Heart, specifically) to the over-the-top performances to the weird subplots (including a neighbor who raises cats for their fur), this film jams its foot on the gas pedal and never lets up. It’s clear that Dwain Esper wanted to take a more economical approach, squeezing as much controversial content into the film as he could, rather than telling a satisfying story, but that’s the point. People can get a good story anywhere. Maniac delivered gratuitous nudity, outrageous violence, and other cheap thrills at a time when audiences couldn’t get it anywhere else, and they could get in and out in less than an hour. Yeah, that’s right. It clocks in at a brisk 51 minutes and the only real time that’s wasted are those minutes spent “educating” the audience on various mental illnesses, which frankly are pretty hilarious on their own.

Of course, Esper continued this trend, later releasing Marihuana, which was just another excuse to depict teenagers committing various acts of depravity and violence disguised as a propaganda film about the dangers of pot, as well as acquiring the rights to Reefer Madness (a legitimate propaganda film) and re-cutting it for the exploitation circuit. Say what you want about him as a filmmaker, but Dwain Esper knew exactly what he wanted and knew exactly how to deliver it, which, at the end of the day, is really all that matters, isn’t it?

Maniac is now in the public domain (as are all of Esper’s films), so it’s available pretty much anywhere, including Mill Creek Entertainment’s 50 Horror Classics box set. But absolutely seek this one out because it’s well worth your time.